X, Y and a hidden syndrome

- Home

- News & Media

- X, Y and a hidden syndrome

Recent techniques have helped those with Swyer’s Syndrome, in which a woman is genetically male but has female

characteristics, give birth. A Meerut woman just became India’s first such known case

After seven years of marriage and no child, 32-year-old Urvashi Sharma (name changed on request) was informed that she was “genetically male since birth”. It, however, took just 30 seconds for her husband to recover from the shock and say, “You are still my wife.” On February 6, Meerut-based “genetically male” Urvashi, who had no ovaries and an infantile uterus, became the first known

Indian with such a condition to give birth to twins.

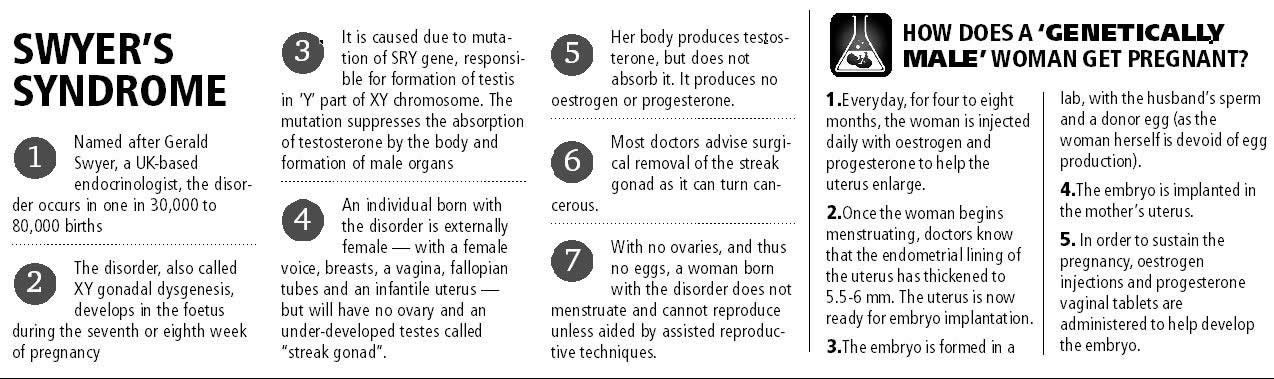

Swyer’s Syndrome, also called XY gonadal dysgenesis, is a rare disorder, occurring in one in 30,000 to 80,000 births. A female has 46,XX chromosome and a male has 46,XY chromosome. A person with this syndrome has 46,XY chromosome and is thus male, but has female characteristics such as female voice, fully or incompletely formed external genitalia, a vagina, under-developed breasts, fallopian tubes and a uterus; but no ovaries. The disorder originates when SRY gene, which triggers formation of male organs through XY chromosomes, mutates during the foetal stage. As a result, testosterone is not produced and the testes is not fully formed. The testes is thus only a ‘streak gonad’, incapable of reproduction.

Urvashi, too, has a streak testes, no ovaries, and thus an extremely rare form of infertility. Till Meerut-based Dr Sunil K Jindal used assisted reproductive technique (ART) to help her conceive. He administered oestrogen and progesterone injections for four to six months, which helped expand her uterus to an almost-normal size. “Once Urvashi started menstruating, it was an indication that the uterus had developed an endometrial lining thickness of 5.5-6 mm, and was ready to nurture an embryo,” says Jindal, adding that periods can start “even without ovum production”.

Once the uterus was ready, the embryo — formed in a lab with a donor’s eggs and the husband’s sperms through the intracytoplasmic sperm injection — was injected into it.

Planting the embryo in the uterus was just half the work done. “Since her body is genetically male and cannot sustain a pregnancy on its own, she was given a daily injection of oestrogen and vaginal capsules for nine months until delivery,” he says. Till now, six other women with XY gonadal dysgenesis have given birth to babies across the world — including in Iceland (1997), England (2007), Serbia (2008), Greece (2011) and the United Kingdom (2015). The most recent case is of 28-year-old Hayley Haynes who gave birth to twins on January 30 this year in the UK. In India, Dr Kamini Rao, the Bangalore-based IVF expert credited with India’s first successful SIFT (Semen Intra Fallopian Transfer) baby which involves external push to sperms to enter the fallopian tube, claims she has four “genetically male” women waiting in line to conceive a baby.

A woman born with XY gonadal dysgenesis does not know she is genetically a man till she reaches puberty and does not menstruate. But that’s only if doctors diagnose the condition. Unlike in the UK, for example, where Haynes learnt of her condition at the age of 19, women in India are not aware of it till they get married and fail to conceive. At the first hint — absence of menstruation — doctors prescribe sympotamic treatment. “When patients complain of not menstruating, doctors give them oestrogen and progesterone tablets that thicken the uterus walls and artificially induce menstruation,” says Rao, adding that the lack of diagnosis has led to “under-reporting of the condition”. No official data, however, exists on the prevalence of the disorder in the country.

Another problem with diagnosing the disorder, says Rao, is the variation in the symptoms. “There are several variations. Sometimes the person may not have lower one-third of their vagina in which case we have to artificially create it. In other instances, the upper portion may not be formed entirely. There are very few characteristics that help in diagnosing the patients. The only factor persistent in all patients of Swyer’s syndrome is the absence of ovaries,” she says.

The condition is diagnosed with karyotyping, a laboratory technique use to map chromosomes. In Urvashi’s case, no expert told her about karyotyping till she consulted Jindal. “Doctors do not consider the possibility of XY chromosomes as the patient has female organs externally. They think the organs are just not fully formed and presence of a uterus, vagina and fallopian tube makes them believe the person is biologically female. The absence of ovaries in the ultrasound image does not encourage karyotyping either,” Jindal said.

A person with gonadal dysgenesis is infertile, but can enjoy a normal sexual life because of the presence of a vagina and other external genitalia.

Jindal, who runs an IVF clinic, says the ART used on “genetically male” women is similar to the one used on post-menopausal women who wish to conceive but can’t as their bodies do not produce enough oestrogen. However, the use of the ART on “genetically male” women is a relatively new idea in India, says Rao, and thus no successful child birth was reported until now. “Urvashi’s case is a great scientific achievement,” says Dr Prakash Trivedi, president of Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecological Societies of India. “The scientific community will follow up on such rare cases and aim to find the karyotype of suspected patients.”

He, however, cautions that “it is not a simple procedure” and not all cases will convert magically into successful births. The first attempt to implant an embryo in Urvashi’s uterus, for example, had failed. On February 6, Urvashi underwent a caesarean and gave birth to a boy and girl, weighing 2.5 and 2.25 kg respectively. Her case study has now been sent for presentation to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, which is meeting at Lisbon, Portugal, in June this year.